Equity in Healthcare:

Healthcare in Black America

“Where We Are”

The Current State of Healthcare in America

By Roderic Walton AIA, NOMA; Associate Principal at Moody Nolan

This blog is the second part of a three-part series about equity (or lack thereof) in healthcare, with a specific focus on Black communities. In Part One “Where We Were” The History of Healthcare in Black America (Franklin, 2020), my colleague Valarie Franklin recounted the history of race and healthcare equity in vivid, intricate detail. Part Two will continue this journey by identifying “Where We Are,” as of September 2020. This essay will endeavor to diagnose the state of current healthcare delivery models by identifying and evaluating obstacles to care that negatively impact, marginalize, and stigmatize Black communities in America. The series will conclude by offering solutions that healthcare architects and designers can employ to position ourselves as conduits for transformational change related to our practice.

SECTION ONE: HISTORICAL CONTEXT FOR TODAY’S DISPARITY

“Not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed until it is faced.” - James Baldwin

Learning objectives for this section:

This section positions the history from Part One into a diagnostic framework of Where We Are. After reading this section, the reader should be able to describe how the disparity in our current healthcare delivery model is a direct result of the history that was established in the Part One essay, and how this history is manifested in today’s healthcare crisis.

COVID-19: CURRENT PANDEMIC

According to the Center for Disease Control, it is now an established fact that the Covid-19 pandemic has resulted in a disproportionate number of positive cases and deaths in marginalized communities throughout the country. “Long-standing systemic health and social inequities have placed ethnic and minority groups at increased risk of becoming ill and dying from COVID-19” (Health Equity Considerations, n.d.). The Covid tracking project reports that “nationwide, black people are dying at 2.5 times the rate of white people” (The Covid Racial Data Tracker, August 2020).

Source: Covid Data Tracking Project

As a healthcare architect, I believe that it is important to encourage candid discussions with coworkers, clients, and partners in the healthcare community and beyond about the contributing factors that drive this disparity. In Part One, Valarie Franklin re-framed the lens on this subject by recounting the multiple eras of discrimination that resulted in centuries of neglect for Black Americans. Today, because of segregated housing policies and structural racism, many Black communities are marginalized and geographically isolated in major metropolitan cities throughout our country. Isolated communities have historically been identified as “high risk” investments and are disenfranchised through community disinvestment. Residents suffer from abject poverty, mental health challenges, and food and transportation challenges. These disadvantages, in turn, result in less frequent engagements with the healthcare system. Preventative healthcare opportunities are limited due to employment challenges and lack of insurance. Healthcare education and counseling opportunities are also more limited. As a result, pre-existing conditions along with comorbidities often go undiagnosed and untreated. Covid-19 is much harder to treat in patients with these underlying health conditions. These factors contribute to social determinants of health, meaning that they determine the level, the quality, and the outcome of care that one receives. In addition, the historical mistrust that Valarie spoke of in Part One was often the result of U.S. government sanctioned experiments by the medical community that were targeted at African Americans. The history of bias against Black patients can make it difficult to trust that the medical community will treat us equally when we need help.

THE PURPOSE OF SEGREGATION

It is critical to acknowledge the history that drives healthcare disparity. To achieve this, I believe that healthcare architects and designers should study the social determinants of health that link housing segregation and access to healthcare. Public housing across the United States was deliberately and aggressively segregated by federal policy, using race, and race alone, as the determining factor of who lived where. Why was this done? The concept of race has historically been confused with genealogy, and ultimately used as means of attempting to “predict behavior” by categorizing Black Americans based on an imagined, yet pervasive evaluation of intelligence, pending actions, and general merit. In everyday social encounters, this type of bias is based almost exclusively on observable physical traits, associated stereotypes, and an over-abundance of imagination and creativity on the part of the observer. This creative speculation is then used to “fill in” what the observer’s eyes cannot see, (i.e. individual merit)in order to complete a mostly self-defined, and therefore inherently fictional image of another human being. The conclusion of this mental exercise is then used to justify the observer’s misguided belief that he is innately superior. Negative connotations related to race, specifically notions of superiority vs inferiority, belie the reality that many Americans today are learning through popular genealogical services. That is, that our actual heritage is in fact far more culturally fluid and mixed than we may have either realized, or desired to know. Rather, Americans in positions of power have historically preferred simple, non-binary and “pure” racial constructs because they ease the justification of racist policy positions targeted at a disfavored class. The portrayal of Black people as poor, dumb, lazy, shiftless, and deserving of simultaneous mocking and fear has been woven into our history in every type of extant media (an example of which is black face). This bias was designed to disguise the individual merits, unique abilities, and collective strengths of Black people. In their work entitled Racecraft: The Soul of Inequality in American Life, Barbra and Karen Fields coin the term racecraft. This concept describes day-to-day interactions that allow racism to exist as a paradigm that marginalizes a physical or imagined trait of a target (i.e. brown skin or laziness). In reality, what is occurring is that the bigoted, biased state of mind of the aggressor (i.e. bias against people with brown skin, or preconceived notions about work ethic) has become so pervasive that it is crafted into legitimate thought, and translated into action or social policy.

“Unlike physical terrain, racecraft originates not in nature, but in human action and imagination. It is a kind of fingerprint evidence that racism has been on the scene” (Fields, K. E., & Fields, B. J., 2016).

HOUSING SEGREGATION

The manifestation of the dynamics of racecraft is that the biased, bigoted mind of the aggressor becomes more dangerous than the person being targeted will ever be. The social engineering of racism into housing policy was executed with precision by the most powerful and influential men in our country at the time. I believe that this was done to codify into law the belief that they were superior human beings. Between 1929 and 1953, U.S. Presidents Herbert Hoover, Franklin D. Roosevelt and Harry Truman advanced racist housing policies and empowered cabinet members who were known to be sympathetic to the cause of segregation. As part of a comprehensive set of social initiatives that would eventually be branded as the New Deal, the creation of the Federal Housing Administration in 1934, and the passing of the Housing Act of 1937 cemented the Federal government’s role as a public housing agency. The racist policies generated by these agencies were combined with state and local ordinances in a concerted strategy to segregate American cities through formal legislation combined with predatory lending practices. The intent was for this segregation to be aggressive and pervasive, and to endure over decades and generations. It was effective, because these policies endured for decades after their implementation, including in both written and unwritten form. In his book The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America, Richard Rothstein clarifies this point in detail:

“Until the last quarter of the twentieth century, racially explicit policies of federal, state and local governments defined where Whites and African Americans should live. Today’s residential segregation in the North, South, Midwest, and West is not the unintended consequence of individual choices and of otherwise well-meaning law or regulation but of unhidden public policy that explicitly segregated every metropolitan area in the United States. The policy was so systematic and forceful that its effects endure to the present time. Without our government’s purposeful imposition of racial segregation, the other causes – private prejudice, white flight, real estate steering, bank redlining, income differences, and self-segregation - still would have existed, but with far less opportunity for expression” (Rothstein, R., 2018).

THE LASTING IMPACT OF RED LINING

The implications of the New Deal and its racist housing policies for today’s healthcare environment are profound. For example, the Homeowners Loan Corporation (HOLC) was created as part of the New Deal as a government sponsored housing agency.

“The HOLC created “residential security” maps for major American cities for use by loan officers, appraisers and real estate professionals that outlined neighborhoods according to investment risk, often redlining black neighborhoods as “hazardous” areas. According to the advocacy group National Community Reinvestment Coalition, “74% of the neighborhoods that the HOLC designated as high risk or “hazardous” are low-to-moderate income neighborhoods today, and 64% are minority neighborhoods” (NCRC, 2019).

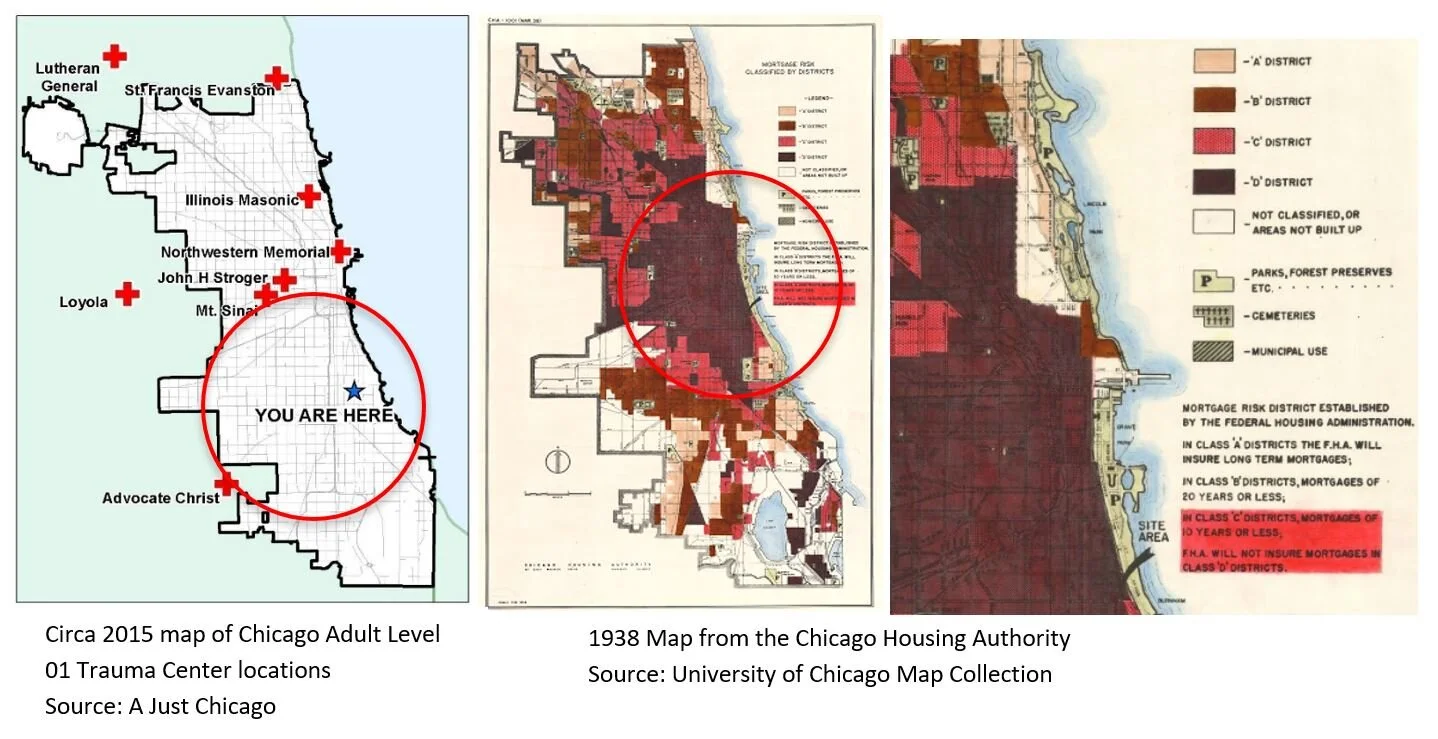

The city of Chicago is an instructive example of housing discrimination, as the implications of red lining and financial disinvestment due to high risk categorization have had a profound impact on the quality of healthcare for Chicago’s South Side Residents. In 2010, eighteen-year-old Damian Turner was shot on the south side of Chicago, just a few blocks away from the University of Chicago’s medical district. Citing financial concerns, the University had closed South Side Chicago’s only Adult Level 1 Trauma Center decades earlier. As a result, Damian could not be admitted to the emergency department nearest to him, as it did not have the Adult Level 1 Trauma designation necessary to treat his wounds and stabilize him for surgery. Instead, the ambulance drove Damian to the closest Adult Level 1 trauma center that could admit him, which was 20 miles away. Damian died on the way there. After years of negotiations with community, local and state agencies, the University of Chicago Medicine agreed to design a new Adult Level 1 Trauma Center. This decision provided the South Side with more accessible trauma care, addressing a health “desert” that had persisted for decades.

The images above show the health care “desert” that existed in South Side Chicago in 2010. It is the same area of Chicago that was redlined as a “Class C District” through racist housing policy decades earlier. Class C districts were not eligible for FHA backed home loans. Opportunities for small business loans in this area were similarly restricted. Financial disinvestment was the result.

IMPACT OF SEREGATION ON HEALTHCARE TODAY

Despite initiatives to combat it, such as the Fair Housing act of 1968, segregation continues to be pervasive in many parts of the country today. Though segregated housing policies are not formally enforced today, a statistical analysis reveals that the effects of structural racism specifically related to segregation and red lining are alive and well in cities across the country. According to Census Scope, “The dissimilarity index is the most commonly used measure of segregation between two groups, reflecting their relative distributions across neighborhoods within the same city (or metropolitan area)” (Census Scope, n.d.).

Source: The Brookings Institution

The segregation index (as well as the dissimilarity index and diversity index) is a metric that is used to measure how evenly distributed two ethic groups are in a particular geographic area. The numerical range progresses from zero (0) meaning that the area is fully integrated, to one hundred (100), meaning that the region is completely segregated. These values are then used to determine the percentage of Black Americans that would have to relocate to a different area to evenly distribute race across that particular region. “Even distribution” is defined as the same percentage of that group as the entire country, based on census data.

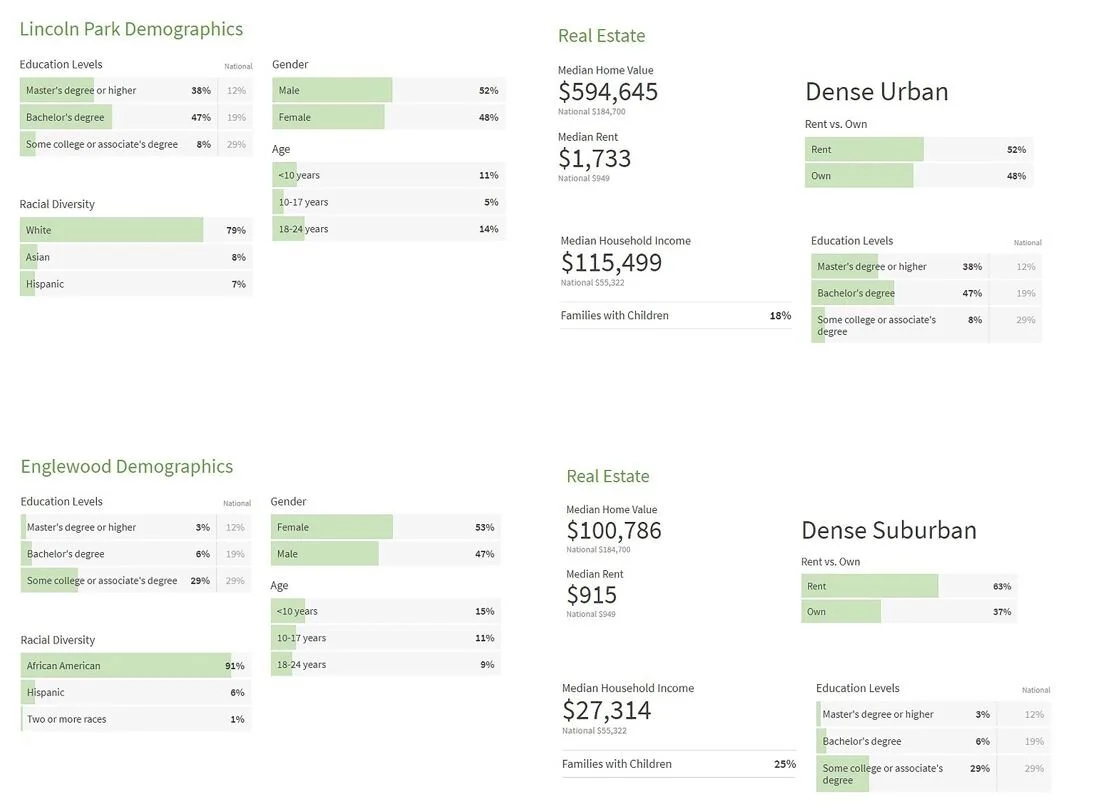

These data reveal that major metropolitan cities throughout the country are still segregated today. As noted previously, Chicago is an example of this impact. In this city, rigidly defined racial boundaries have persisted for decades. Chicago has one of the highest dissimilarity indexes in the country, typically hovering above eighty percent. To place these data in familiar context, let us explore two areas in Chicago in greater detail. Lincoln Park and Englewood are two community areas of Chicago which are only twelve miles apart, a twenty-minute drive in normal traffic. However, they are essentially different worlds when the demographic composition is evaluated:

Source: www.niche.com

The numbers reveal that when housing is segregated by race the effects are profoundly devasting. Black segregated communities that exist today and which are the direct result of the social policies mentioned above have a lower per capita income than any other community. They also suffer from significant disparities in median home values, as well as education. Many of these residents are living at or only marginally above the poverty line. Segregated housing in 2020 impacts the type of education one receives because most schools in the U.S. are funded by property taxes, so poor communities have poorly funded schools. This educational disparity is a driver for wealth gaps. With specific regard to healthcare, segregated housing in 2020 impacts the type of healthcare one receives because isolated housing drives virtually every other social determinant of disparity.

CONCLUSION

There is no evidence-based case that supports the notion that one race in America is uniquely gifted, exceptional, or of superior intellect. Conversely, every race and culture consist of intellectual equals. Despite this truth, a study of history reveals that racist housing policy was used to engineer segregated communities in the U.S. over the course of many decades, with the deliberate intent to marginalize them. The artifacts of these racist policies are not just relegated to history. Today, isolated Black communities around the country have been hit the hardest by Covid-19. As a Black man who is also a son, brother, father, husband, and potential patient, I am fearful of how I or someone I love will be perceived and treated when they enter the healthcare system in pursuit of compassionate care. As a Black man who is also an architect, I am optimistic that our future as a country can be much brighter than our past. Part Three of this blog series will focus on “Where We Hope To Be” by offering solutions related to advocacy and practice that healthcare designers can take to effect change.

Roderic has twenty-five years of experience in building design, is a licensed architect, and has practiced in both Ohio and Illinois. Most of his portfolio is focused on healthcare projects.

Roderic has dedicated his career to addressing the needs of healthcare clients and the communities they serve, with particular focus on those in under-served and disadvantaged areas in the south side of Chicago, Illinois.

Roderic holds a master’s degree in architecture from Miami University in Oxford, Ohio, and actively participates in both local and national organizations including NOMA, AAH and AIA.

He is currently an Associate Principal at Moody Nolan Architects.

The thoughts and opinions reflected in this blog are the authors’ own, and do not reflect the views of any firm or other organization.

Work Cited:

Census Data, Charts, Maps, and Rankings. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://censusscope.org/

Fields, K. E., & Fields, B. J. (2016). Racecraft: The soul of inequality in American life. London: Verso Book.

Franklin, V. (2020, June). Where We Were; The History of Healthcare in Black America [Web log post]. Retrieved August 8, 2020, from https://www.nomanash.com/healthequity

Health Equity Considerations and Racial and Ethnic Minority Groups. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/community/health-equity/race-ethnicity.html

Ncrc. (2019, July 25). 24/7 Wall St.: 25 most segregated cities in America " NCRC. Retrieved from https://ncrc.org/24-7-wall-st-25-most-segregated-cities-in-america/

Rothstein, R. (2018). The color of law: A forgotten history of how our government segregated America. New York: Liveright Publishing Corporation, a division of W.W. Norton & Company.

The COVID Racial Data Tracker. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://covidtracking.com/race

READ MORE

BACK TO PART 1 IN THIS SERIES: HEALTHCARE IN BLACK AMERICA - WHERE WE WERE

GO ON TO PART 3 IN THIS SERIES: HEALTHCARE IN BLACK AMERICA - WHERE WE HOPE TO BE